We all know the health benefits of exercise. At a minimum, regular exercise is the gift that keeps on giving to the tune of improved brain health, help managing weight, reducing risk of disease, strengthening bones and muscles, and improving your ability to do everyday activities. That sounds so great, so what’s stopping us from leaping out of bed to do it every day?

Your brain.

It turns out that there are several theories at work around why you don’t want to work out, and they’re all in your head. But not in a dismissive way. It’s real and here are four reasons why researchers say you don’t want to work out, even when part of you does.

Procrastination

Let’s say you have a big project due. You know the due date. You know you’ll get paid when it’s done. Yet you don’t do it until the very last minute (or maybe even after that). Working out can be the same. You’re fighting with yourself over resources.

“It’s self-harm,” Dr. Piers Steel, a professor of motivational psychology at the University of Calgary and the author of “The Procrastination Equation: How to Stop Putting Things Off and Start Getting Stuff Done” told The New York Times. That’s why it feels so bad when you realize you’re doing it. You’re aware that you should work out (or fold the laundry, finish that project for work, etc.) but are choosing not to. Here’s what another doctor told writer of the same article in the Times:

“This is why we say that procrastination is essentially irrational,” said Dr. Fuschia Sirois, professor of psychology at the University of Sheffield. “It doesn’t make sense to do something you know is going to have negative consequences.”

She added: “People engage in this irrational cycle of chronic procrastination because of an inability to manage negative moods around a task.”

We put things off because it doesn’t feel good, and we can’t get past it.

Maybe that work project is boring, or time consuming. We don’t put off eating ice cream, right? Or watching movies. You never hear someone say, “I’ve been meaning to play my new video game.” That’s because all the pleasure centers in your brain get a payoff with those activities. There’s no friction to get over.

“Procrastination is an emotion regulation problem, not a time management problem,” said Dr. Tim Pychyl, professor of psychology and member of the Procrastination Research Group at Carleton University in Ottawa in the same article. When you can’t get past the idea that you might need to work through physical pain, fatigue, or boredom, you put off the task. Working out requires enough freed up energy to take it on. If you’re feeling tired or frustrated, burdened by self-doubt, your brain is busy focusing on that. You’re not necessarily lazy. You’re distracted.

You’re hardwired to reserve your energy.

That’s what Harvard professor Daniel Lieberman, an expert in human evolutionary biology, posed in a 2015 paper, “Is Exercise Really Medicine? An Evolutionary Perspective.” Your human instincts are trying to protect you against future hunger, be it from famine, drought, war or natural disaster. Your brain doesn’t know about grocery stores and cars, and it’s certainly in the dark when it comes to expending calories on purpose.

“It is natural and normal to be physically lazy,” he writes. “… I predict that hunter-gatherers in the Kalahari or the Amazon are just as likely as 21st century Americans to instinctively avoid unnecessary exertion. Although a small percentage of people today exercise as a form of medicine, doing their prescribed dose, the vast majority of people today behave just as their ancestors by exercising only when it is fun (as a form of play) or when necessary.”

Our ancestors had a hard time building up enough food reserves to make up for all the effort it took to hunt down that food in the first place. Conserving energy was a life or death decision. Today, most of us are lucky enough not to wonder where our next meal comes from, the one that will make up for the calorie deficit created by exercise.

“It didn’t matter because if you wanted to put dinner on the table you had to work really hard,” Lieberman said in an interview with the Washington Post. “It’s only recently, we have machines and technology to make our lives easier. … We’ve inherited these ancient instincts, but we’ve created this dream world and the result is inactivity.”

You had bad childhood experiences with exercise.

Still another theory comes from Bradley Cardinal, a professor at Oregon State University with an expertise in psychosocial and sociocultural aspects of health and physical activity. He believes that childhood trauma (or success) may set the groundwork for how active you are as an adult.

In a 2013 study, he discovered that those with a negative experience around physical activity as children (think being picked last for a team), tended to exercise less than those who didn’t have that experience.

It’s not fun.

Even our ancestors could be persuaded to burn calories for games, dances or other social events. But in today’s society, play gets stripped out of life as we age. There’s certainly no recess for adults, and even going out dancing tends to wind down by your thirties. Our society values work, which tends to be sedentary. Working up the energy to buck the trend, all in order to go spend more energy is a big ask.

What’s the solution?

Most researchers, doctors and trainers agree that working out is an uphill battle against our evolutionary traits. It’s worth the fight, but our strategy may have been wrong so far. Going back to the idea about procrastination being an intellectual response to discomfort, then compounded by shame, isn’t helping. No wonder working out can feel like a chore.

What if we stopped berating ourselves and started accepting that working out is absolutely against our human instincts? Exercise has incredible health benefits, and there’s no denying it. But it’s the psychological aspect that we might need to tackle first. In order to untangle the negative associations we’ve built around exercise, it’s going to take a softer touch.

Here’s how to motivate yourself to work out:

- Be kind to yourself.

- Set a realistic goal for working out and congratulate yourself when it happens.

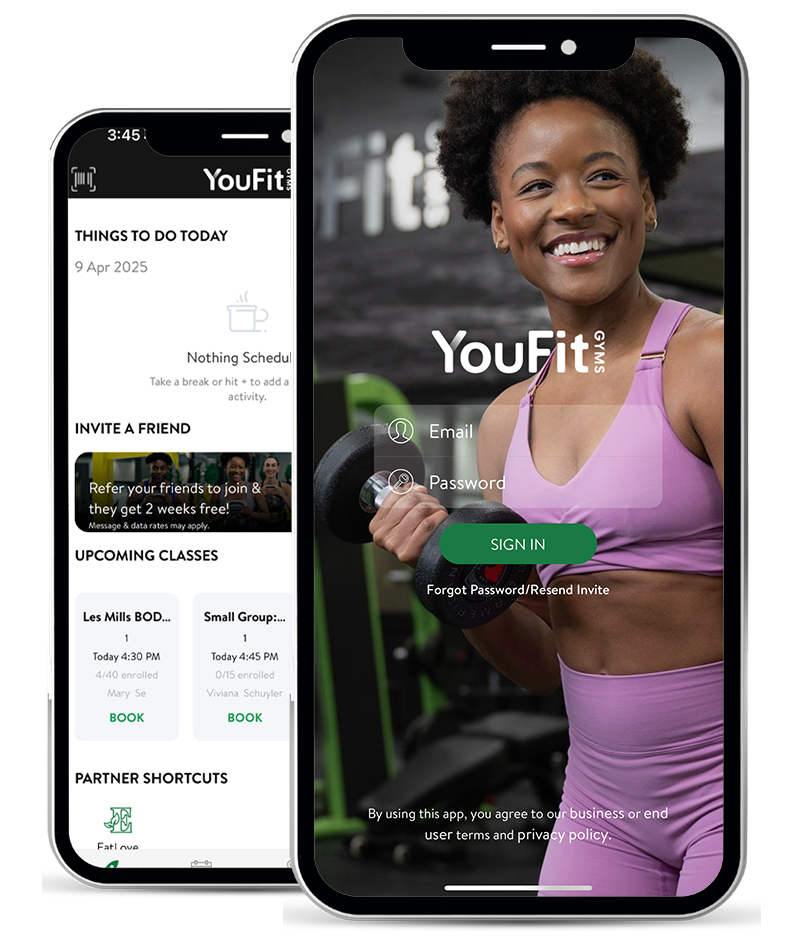

- Make it fun! Try different classes like Zumba, HIIT+, yoga and more. You might be surprised at how much personal attention and a fun soundtrack changes the experience.

- Get a workout partner. Research shows that the number one predictor of getting in shape is having a partner. For the social aspect as well as the accountability.

Above all, don’t be so hard on yourself. Get more enjoyable activity into your day in little bits: walking after dinner, stretching during TV shows, or even throwing a ball to a pet can add up to more pleasant experiences, the kind that re-train your brain to enjoy activity instead of resist it.

YouFit is here to help! We offer dozens of classes – both in person and online – to help make exercise fun. Our personal trainers can also set up routines that accomplish what you want: from better balance to bigger muscles or more energy to get through the day. Find out what’s possible at your nearest location now.